Story by Jack Croft

Illustrations by Saratta Chuengsatiansup

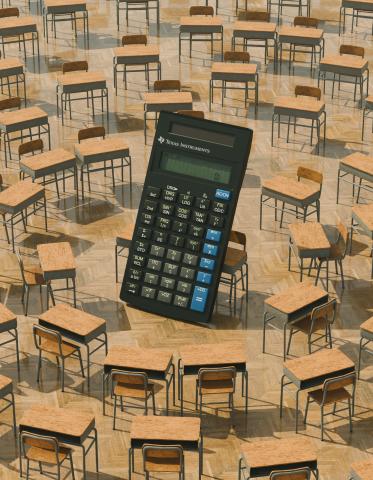

Four decades ago, in April 1986, a group of math teachers picketed during the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics annual meeting to protest the council’s recommendation to integrate calculators into math programs at all grade levels, including elementary school.

The protestors carried signs like “The Button’s Nothin’ Til the Brain’s Trained” and “Beware: Premature Calculator Usage May Be Harmful to Your Child’s Education,” according to a Washington Post account. But the 40,000-member council’s president-elect at the time, John A. Dossey, said the recommendation was for children to learn how to use a calculator after they were taught the fundamentals of how to do math.

“Children in a modern society have to learn to use modern tools,” Dossey said.

With all the controversy, consternation and claims surrounding the advent of generative artificial intelligence, some Lehigh University College of Business faculty believe that history may be repeating itself.

“A long time ago, people had to do their mathematical computations by hand. And then somebody came up with a calculator, and that allowed them to do things quickly, and took a lot of the laborious plug and chug out of it,” says McKay Price, professor and department chair in the Perella Department of Finance.

“AI is a similar situation. Like the calculator, it’s another tool. Our students need to be able to use the tool appropriately, effectively and efficiently. They’ll be expected to use it when they get out into the workplace.”

Bright Asante-Appiah, assistant professor of accounting, agrees. “Business school educators, whether we like it or not, have a responsibility to adopt teaching methods that prepare students for a future where AI will play a significant role in the workforce and society,” he says.

What are the main opportunities and challenges generative AI poses?

OpenAI’s launch of ChatGPT in November 2022 was met by about the widest divergence of opinions conceivable, from predictions that it would usher in a utopian future of peace, health and prosperity to those who foresaw a dystopian future where the new technology would pose an extinction threat to humans. Most experts fell somewhere much closer to the middle of those opposite predictions.

“I think with generative AI, we’re still in a sense-making process,” says Michael Rivera, assistant professor of Business Information Systems in the Decision and Technology Analytics (DATA) department. “We’re trying to get our heads around full-scale capabilities. What do I need to do as a human or an employee? And how can this AI enable me to live my life or complete my work better? These are unchartered waters.”

“I would say that like a lot of these new technologies, disruptive technologies, we tend to see patterns that replicate themselves in history. AI-driven change is going through a technology adoption life cycle, much like we would have seen with the internet or mobile communication life cycles.”

Among the opportunities Lehigh Business School faculty see are:

Increased efficiency and productivity.

Empowered employees who can focus more on creative solutions rather than routine and repetitive tasks.

Advanced life-saving protocols, diagnosis of disease and development of prescription drug breakthroughs.

Increased ability to identify potential opportunities and risks in financial planning.

Improved and more personalized customer engagement.

More power to harness the staggering amount of data needed for generative AI systems to help us solve complex and intransigent global problems, such as climate change and poverty.

The challenges, however, are also plentiful and daunting, including:

Likelihood of job loss for more vulnerable workers.

Increased spread of misinformation and “deep fake” images, videos and recordings.

Further erosion of privacy.

Potential for plagiarism and/or intellectual property infringement as a result of the data used to train generative AI systems.

Increased instances of human biases from past decisions, in areas such as hiring and real estate, that could creep into generative AI outputs.

And that doesn’t even include “AI hallucinations,” the disturbing tendency generative AI has to sometimes make things up, including creating fictitious names and even non-existent academic journals and articles as sources.

At Lehigh and every other academic institution, there are specific opportunities and challenges for how faculty and students use generative AI in teaching and research. Students absolutely need to know about the rapidly developing technology of generative AI as they graduate and enter the workplace.

“Things have changed, but they haven’t changed,” Rivera says. “The greatest value for any of our students in earning a degree and entering the workforce is to have the skills to solve organizational problems. We’re going to try to figure out how we can leverage AI in a technology-

enabled way as a primary tool in their toolkit, both for work and life.”

Generative AI and Teaching: Modern Tools for a Modern Society

Having overcome initial reservations about allowing students to use ChatGPT and other generative AI tools, many Lehigh Business School faculty are now incorporating generative AI into their teaching.

“The only thing I think a teacher can do is let their students know that this is a tool that can be used to either learn more or to not learn,” says Fabio Gómez-Rodríguez, assistant professor of economics. “It’s up to the students themselves to determine how they want to use AI technology. I think forcing your students not to use some available technology will only backfire. Technology is there to be used, and it’s our role to guide our students to use something like AI as productively as possible.”

Kofi Arhin, assistant professor of DATA, teaches the course AI for Business. “In my class, we explore the challenges, risks, benefits and opportunities of using AI technology,” Arhin says.

“Last semester in class, we had access to a dataset for a superstore and used generative AI to analyze the data. There were four managers in the superstore. We asked the generative AI system to list all the managers in the superstore, and it gave us five names. It made up a fifth manager name, and we were like, ‘Wait, this name is so real. Where did you get it from?’ And this name was nowhere in our data. There’s a concern that AI can produce inaccurate information and, in essence, hallucinate.

“The students have to learn about all these challenges in using this tool that is not perfect. For the most part, AI is a valuable tool, but inaccurate information it might produce could bring a lot of trouble or create harm. That’s a key issue here. You should never take the content AI produces as a final product under any circumstance or scenario,” Arhin warns.

During the spring 2024 semester, Beibei Dong, who holds the George N. Beckwith ’32 Professorship in Marketing, introduced generative AI into two of her classes: a marketing foundation class with mostly first-year and sophomore Lehigh Business School students, and a service innovation course for upper-level students.

“I wanted the students to experience how AI is used in marketing,” Dong says of the foundation class.

She had the students brainstorm new product ideas and use generative AI to develop and design new product prototypes. Then, the students were asked to create marketing campaigns for the product, generating advertisements, Instagram posts, a blog and a podcast—using AI.

“The students were amazed with what AI can do,” Dong says.

At the same time, students realized that in order to use AI effectively, they needed to learn about how to write strong prompts to get the outputs they were seeking. They saw, firsthand, the limitations of AI, including hallucinations.

“This experiment was helpful. The students understood how AI can be used in marketing, but they saw how humans are not replaceable in the marketing process,” Dong says.

For the service innovation class, students used a McKinsey & Company report on the industries that are most affected by AI, and picked six industries to study, ranging from healthcare and computer science to marketing and journalism. Students conducted a deep analysis of how AI is affecting performance, productivity and job market employment in the specific industries, including whether human workers are being replaced short-term or long-term and the impact AI is having on big companies compared to small businesses.

“The students came back with a lot of useful information,” Dong says. “I learned a lot from their investigations myself. We held a debate at the end of the class to summarize all that we had learned, and comparing the pros and cons of generative AI use in society.”

K. Sivakumar (“Siva”), who holds the Arthur C. Tauck, Jr., Chair in International Marketing and Logistics and serves as chair of the marketing department, says the question of how humans interact with machines is the one he finds most interesting now.

“I always tell students that I really am agnostic about whether somebody is using AI in my class or not. I am particular, however, in demonstrating the value added by human beings,” Siva says. “It is perfectly OK to use any of these tools because the tools are there; we have to use them. But, if we are not able to demonstrate our added value as humans, then I will not have a job. Students will not have jobs.”

Faculty are using AI to enhance their teaching.

Liuba Belkin, who holds the Thomas J. Campbell ’80 Professorship in Management, revamped her curriculum for the 2023–24 academic year, eliminating a lot of writing for students and putting more weight on in-class simulations.

Among several ways she added interaction with AI to her classes was to have the developer who built the simulation platform she uses for negotiation exercises add an AI component for the MBA-level leadership class. Belkin fed the AI the slides and materials she used for the class so students could interact themselves with AI on leadership topics, such as conducting difficult conversations with employees at work.

“I was blown away with the quality of advice AI was giving to students,” Belkin says. “AI’s ability to synthesize large amounts of information and tailor advice for various situations and organizational needs is superb. MBA students taking this course all have real-life work experience and many of them hold managerial or supervisory roles while enrolled in the course. They really loved this tool and found the interaction helpful. I’m definitely using it again next semester and perhaps developing it further to incorporate other topics and exercises, making the entire learning experience more valuable and fun.”

Andrew Ward, who holds the Charlot and Dennis E. Singleton ’66 Chair of Corporate Governance and is the management department chair, teaches a class on societal shifts and how they connect to what he calls The Great Divides (Wealth, Health and Technology).He is now having students create a video on the topic using generative AI tools.

“It allows us to do things that couldn’t be done before,” Ward says. “Students use a generative AI tool to produce a script. Next, they use a generative AI video tool to create a video. Two years ago, video creation was much more complicated, requiring multiple video tools and access to video libraries.”

Generative AI and Faculty Research: Risky Business?

As enthusiastic as Lehigh Business School faculty are about incorporating generative AI into their teaching and coursework, they tend to be considerably more skeptical about using it in conducting academic research—at least at this stage in AI development.

However, they are far more open to making generative AI the focus of research projects.

Three Perella Department of Finance faculty members—McKay Price, department chair and Webster A. Collins and Murray H. Goodman Chair in Real Estate Finance, Don Bowen, assistant professor, and Ke Yang, associate professor, as well as Luke Stein, assistant professor of finance at Babson College—recently worked on a study examining racial bias in many common generative AI platforms, such as ChatGPT.

The impetus for the project came from a pilot study conducted by the 2023 FinTech Capstone Group, led by Bowen.

In the broader study, the researchers treated the generative AI platforms “like they were banks or mortgage brokers,” Price says. The researchers fed real-world mortgage application data, which is publicly available through the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act, to the platform and only manipulated two variables: the applicant’s credit score and race. All other variables were held constant. (See Biz Quiz.)

And they only asked AI to make two decisions: Would they approve the mortgage? If so, at what interest rate?

“What we found is that ChatGPT and the other models out there make biased decisions,” Price says. “A Black applicant is more likely to be rejected than a white applicant. Similarly, a Black applicant is more likely to be quoted a higher interest rate than a white applicant. It’s happening across the board, but it’s happening more so when people have lower credit scores.

“There are a lot of arguments for automating these underwriting AI systems—it’s faster, more efficient and can save a lot of money. In theory, it could do so in an unbiased manner,” he adds. “But what we’re pointing out with this research is that you’ve got to be careful because depending on how the AI systems are trained, there is potential for bias.”

The researchers did, however, find one approach to mitigate bias: “We found that if we specifically tell these large language models, ‘You should use no bias in your decision-making,’ that a lot of the bias goes away. But it has to be told. Isn’t that bizarre?”

Through two tech analytics-based companies he co-founded, Michael Rivera works with industry clients to find solutions to technology issues. “In my work, I’ve found a good model: I take the data we generate from client solutions; I anonymize it and then I publish about it and incrementally build my research pipeline.

“A lot of what I’m doing now is around generative AI feedback between employees,” Rivera says. “How can machines be used to enhance feedback? Do you need human intervention to provide feedback that is impactful? I have a whole burgeoning area right now that I’m working on building out.”

Several faculty members say that for research purposes, generative AI is primarily of value in brainstorming, or idea generation, at the beginning of a project and copy editing toward the end. Due to the limitations of generative AI, especially with the hallucination issues and potential for unwitting plagiarism due to the data on which the generative AI is trained, faculty are reluctant to rely on it for key parts of their own published research.

“AI introduces new risks that faculty need to understand and manage,” Asante-Appiah says. “AI can return incorrect information and violate some privacy standards. If you don’t take care, AI can perpetuate biases in your research and possibly present some ethical dilemmas down the road. This is the reason why I have tried to stay away from using generative AI until I see clear and concrete guidelines provided by the profession.”

Because generative AI is trained on massive amounts of existing data, it reflects only what has happened in the past, rendering it less useful for faculty seeking to contribute to new knowledge.

“As a researcher, I am interested in finding a gap and then addressing a gap,” Siva says. “These tools are not very good at knowing what is not there. As a researcher, it is my job to find out what has not been studied and conduct research on that.”

Listen to our podcasts about AI.

What’s the difference between AI and generative AI?

Stanford University computer scientist John McCarthy coined the term “artificial intelligence” in 1955, defining it as “the science and engineering of making intelligent machines.” However, work in the field dates back into the 1940s, possibly earlier, with pioneering discoveries in the development of artificial neural networks.

Where traditional AI systems are “designed to recognize patterns and make predictions,” the World Economic Forum notes, generative AI “uses machine learning algorithms to create new and original content like images, video, text and audio.”

The Human Touch

What makes people irreplaceable?

Beibei Dong, who holds the George N. Beckwith ’32 Professorship in Marketing, believes that to ask that question is to answer it.

“I would say to be a human is what would make you truly irreplaceable in the future,” Dong says. “When machines become smarter, the best thing we can do as humans is to be a human. What does that mean? It means that we need to use human skill sets that AIs don’t have, skill sets that machines don’t have.”

Those skill sets include human intuition, which develops over time; a holistic viewpoint; the ability to see the big picture—how things are interconnected; and contextual understanding, “especially in situations that are ambiguous and the path forward is unclear.” Dong says.

Fabio Gómez-Rodríguez, assistant professor of economics, agrees. “I think, in the end, humans will always have to provide the creativity in this equation. Humans are amazing at evolving and creating new stuff,” he says. “I understand how how humans might be afraid of AI. Will humans at some point be unnecessary? But I think we have shown repeatedly that people cannot be replaced. We just find new ways to express ourselves and express our ideas.”