Story by Mary Ellen Alu

Illustrations by Dan Page

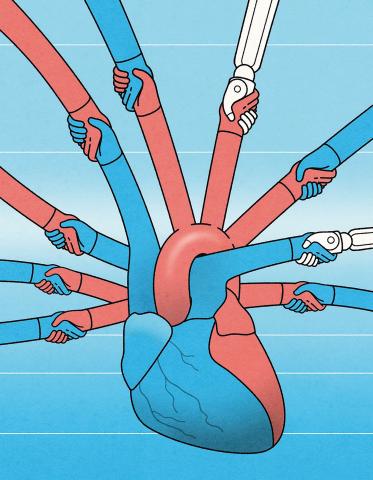

Would a fee-for-service Medicare dental benefit save healthcare costs and lead to a reduction in heart disease among beneficiaries?

Can artificial intelligence improve healthcare by more accurately diagnosing illnesses? Can a data-driven approach improve diabetes care by guiding when patients are scheduled to see doctors, especially those most at risk of slipping through the cracks?

Critical and consequential, such questions are among those driving the healthcare-related research of Lehigh Business faculty in three key areas: the effectiveness of interventions on overall health, the efficiency of hospital organizations in delivering care, and the accessibility of healthcare services to all population groups. Oft cited by government and policy organizations, this area of research can help guide government policy decisions and influence how tax dollars and resources are allocated.

“Healthcare services tie directly into people’s wellbeing, and it becomes increasingly important as you age,” says Chad D. Meyerhoefer, who holds the Arthur F. Searing Professorship and chairs the Department of Economics.

“People who have good access to healthcare live significantly happier, healthier, longer lives than people who have poor access to healthcare.”

Recognizing the need for health industry leaders who understand the issues that shape community health and promote health equity, the College of Business has joined with the College of Health in launching a new undergraduate interdisciplinary education program—the integrated degree in business and health (IBH). The program, launched in Fall 2025, combines the core principles of business with in-depth study of the healthcare system and policies.

Undeniably, healthcare is big business.

In the past several decades, healthcare spending in the United States has climbed, with total spending increasing by 7.5% in 2023 to reach $4.9 trillion, or almost 18% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), according to the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. Healthcare spending is projected to reach 20% of the GDP by 2033.

Additionally, some 22 million people work in the industry, according to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

“You’re looking at nearly one-fifth of all the wealth of the country devoted to supplying healthcare,” Meyerhoefer says. “That’s a lot. It’s hard to name any other homogenous sector that consumes such a large fraction of the nation’s wealth.”

Measuring Health Outcomes

Among the breadth of research are faculty studies that examine the impact of healthcare interventions on patients’ wellbeing.

Consider Meyerhoefer’s research into the high cost of obesity, as new GLP-1 medications gain significant attention for their role in treating diabetes and promoting weight loss, and as policymakers and insurers calculate the cost-effectiveness of such interventions to prevent and treat obesity. The research, published in the Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, brought new understanding to the obesity epidemic and its costs.

Meyerhoefer and his colleagues from Cornell University, Lafayette College and Novo Nordisk, Inc. found that the medical costs of obesity in the United States were much higher—nearly $316 billion a year—than previous studies had shown.

The greatest savings occurred when those who were morbidly obese and suffering from diabetes lost 5% to 10% of their body mass index.

The team found that a 5% reduction in weight led to an estimated savings in annual medical care costs of $2,137 for those with a starting BMI of 40; $528 for those with a starting BMI of 35; and $69 for those with a starting BMI of 30. (BMI of 30 or greater is considered obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

The team’s research has been cited by the American Heart Association, the National Academy of Medicine, the Joint Economic Committee of the Congress and the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

Currently, Meyerhoefer is leading research into the impact of poor oral health on heart disease. The team, which includes colleagues from the University of Maryland Dental School and the University of Michigan, expects to inform policymakers who are considering a fee-for-service Medicare dental benefit. The methodologically complex study is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

“It’s the over-65 population that we’re interested in, because there’s no dental insurance benefit in Medicare other than limited coverage available through some Medicare Advantage plans,” he says.

“The question is, if you started covering dental insurance broadly under Medicare, would it actually save costs and reduce the adverse effects of chronic conditions such as heart disease?”

Meyerhoefer says he and his colleagues are using genetic data from the UK Biobank, a large-scale biomedical database, and the U.S. Health and Retirement Study, a nationally-representative longitudinal study of older Americans, to disentangle patient behaviors and access to healthcare from oral health and chronic disease to assess causation.

***

Meanwhile, Muzhe Yang, who holds the Charles William MacFarlane Professorship in Economics, has focused his research on environmental factors that affect maternal and infant health. In a key study, Yang and Dhaval M. Dave, of Bentley University, examined the connection between pregnant women’s exposure to lead-contaminated drinking water and their newborns’ subsequent health.

The researchers leveraged a unique natural experiment that grew out of a water crisis in Newark, New Jersey, in 2016, when high lead levels were found in drinking water. A year earlier, one of two water treatment plants had increased the acidity level of its treated water, unintentionally reducing the effectiveness of the corrosion inhibitor it used to control lead release. As a result, lead from plumbing fixtures had seeped into the water, exposing homes serviced by that plant to the higher lead levels.

Using data on all live births in New Jersey between 2011 and 2019, the researchers found the prenatal lead exposure increased the chance of low birth weight by about 18% and also increased the chance of preterm birth by about 19%. The research was published in the Journal of Health Economics.

What happened in Newark may have been “the tip of an iceberg,” Yang says. He pointed to other U.S. cities in which high levels of lead were found in drinking water, including Baltimore, Chicago and Detroit.

“The main policy implication of our study is that replacing all lead water pipes being used in the U.S. water system should be done as soon as possible,” Yang says in an interview in the Lehigh Business IlLUminate podcast. “It is not a question of whether we should do it or not, but a question of how quickly we can do it.”

Measuring How Organizations Perform

Lehigh faculty also have focused attention on another critical area—how hospitals, nursing homes and other health institutions perform, including whether the use of AI can improve patient care. How might operational differences affect health outcomes and access to care?

With an alarming surge in hospital data breaches in recent years, Lehigh graduate student Dapeng Chen, with two faculty members—David Peng, who holds the Dean’s Chair Professorship in Decision and Technology Analytics, and Shin-Yi Chou, who holds the Arthur F. Searing Professorship in the Department of Economics—set out to examine the impact on the quality of patient care at the affected hospitals.

The hacking incidents had laid bare the hospitals’ vulnerabilities, and in the process compromised sensitive health information, as well as the Social Security numbers, of millions of patients. The incidents also cost the breached hospitals millions of dollars in ransoms, data recovery efforts and class action lawsuits.

“We all want to have some kind of assessment of the magnitude of a data breach, because if you don’t know the impact, then you probably don’t know how much to allocate for corrective actions,” Peng says. “Just having a rigorous evaluation of the impact itself has value.”

The researchers examined hospital-level data breach reports from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and patient-level hospitalization records from the Florida State Inpatient Database, from 2013 to 2017. Their primary analysis covered nearly 1.3 million records of patients admitted through the emergency rooms at 12 hospitals in Florida.

In doing so, the team found a silver lining: The data breaches led to improvements in the quality of patient care at the breached hospitals.

In the long-term, the hospitals saw a 10% reduction in the amount of time patients spent in emergency rooms before being admitted, and an 8% decrease in the number of days until patients underwent principal procedures after being admitted to their institutions, according to the data analysis led by Chen.

Most significantly, for patients who had suffered acute myocardial infarctions, there was a 10.7% reduction in in-hospital mortality rates. The mortality rates for other patient groups remained unchanged. The research is published in Health Services Research.

While the findings may seem counterintuitive, Peng and Chou say, they’re actually not.

“There are several reasons that hospitals might improve,” Peng says. “If your system got attacked, naturally that means your hospital IT systems probably have some holes. So, with that, the breached hospital will have to improve its hospital IT system. You have to also redesign the workflow and the processes that go along with the IT system.

“The other thing is that, with these kinds of incidents, the Department of Health and Human Services will monitor the affected hospitals for about three years, just to ensure that the implementation of the proactive actions happen. So, there is an external force pushing the hospital to make changes and therefore there are improvements.”

Chou says the team utilized the conceptual framework of failure learning theory to explain how data breaches might lead to better health outcomes. “For any organization, if it wants to survive, it needs to learn from its failures, and then, further improve its operations,” she says.

The team hopes to broaden its research to include hospitals in other states, given the increasing frequency and volume of data breaches. “A more comprehensive understanding of these impacts will help healthcare providers mitigate negative consequences and capitalize on opportunities to improve healthcare quality,” they wrote.

***

As AI continues to rapidly transform many aspects of everyday life, what impact will it have on patient care?

For Rebecca Wang, who holds the Class of ’61 Professorship in Marketing, the question was personal. As she watched her mother undergo cancer treatments several years ago, she wished for more standardized procedures for her mother to ensure the best quality care.

“She was the type of patient who didn’t like to challenge her care providers. She went along with whatever the physicians and nurses decided to do or not to do without any questions,” says Wang, who previously worked as a data engineer at a healthcare software-as-a-service company in Massachusetts. “I observed a huge discrepancy between the kind of care she received compared to patients who were more vocal. That made me wonder, maybe that’s where AI can come into play, that’s where AI can help.”

She consulted with behavioral researchers Lucy Napper, assistant director of the Health, Medicine and Society program, and Jessecae Marsh, associate dean for Interdisciplinary Programs & International Initiatives, both in Lehigh’s College of Arts and Sciences; and Matthew Isaac of the Albers School of Business and Economics at Seattle University.

“Recognizing that there were a myriad of topics and applications of AI in healthcare that we could explore, we chose to investigate whether there would be situations where patients would prefer AI healthcare over human healthcare,” she says. “Previous research suggests that humans are hesitant toward adopting AI technologies, especially in healthcare contexts. So, we ask, is there a way to mitigate this resistance? We came up with the notion of bias salience, that is, if we make people more aware of the biases that humans inherently have, might they actually trust AI more?”

First, in a pilot study, the researchers assessed whether people associated bias more with human providers than with AI. They do, as the researchers suspected. In subsequent studies, the researchers informed participants of biases, asked them to reflect on gender or age biases they had encountered, or asked whether they preferred care from an experienced nurse or one less experienced but aided by AI. They also asked: Why did you pick what you picked?

Those who preferred humans over AI tended to focus on experience and emotions, with one participant saying, “I would rather die from human error than a bug or glitch.” Those who preferred AI, including a participant who had been misdiagnosed in the past, tended to focus more on information in making their decision.

If, however, participants were reminded that biases are inherent in people’s decision-making, they were more receptive to AI in healthcare settings.

“I’m not saying AI technologies are definitely always fairer than humans,” Wang says. “I’m saying that by making patients aware that human doctors or human providers can be biased, we can mitigate patients’ algorithmic aversion toward medical AI.”

Wang says the study also gives those who develop AI systems clearer direction. “If fairness is something that patients value in an AI system, then engineers developing or improving these systems should prioritize it. Beyond medicine- or care-related functionality, they need to ensure that the AI’s decisions are fair.”

Measuring Access to Healthcare

Another key research area centers on individuals’ access to healthcare services, which is critical to maintaining one’s wellbeing and promoting community health.

New research by Han Ye, associate professor of Decision and Technology Analytics, and colleagues examines whether a data-driven strategy can improve care for diabetes patients, especially among high-risk patients in underserved communities.

Managing diabetes and other chronic illnesses is challenging, say Ye and co-researchers. For one, it requires health providers to commit resources over a long duration. For another, it requires patients to actively manage their own health status and interact with healthcare providers.

The researchers collaborated with a multi-facility clinic network in central Illinois that was seeking ways to better manage care and improve patients’ health outcomes.

“A clinic manages a population of patients that come from very diverse backgrounds,” Ye says. “The patients have different demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, and because of that, they might have different engagement behaviors.”

In analyzing clinical and demographic data for more than 10,000 patients, the team found a significant disparity: Those from lower socio-economic communities were less likely to regularly engage with healthcare providers, despite having higher glucose levels. “We were surprised to see that a lot of high-risk patients had zero encounters with healthcare professionals in a six-month time period,” Ye says.

In recognizing that better care management could improve health outcomes as well as reduce costlier emergency room visits and hospitalizations, the team proposed a data-informed decision framework to predict patients’ future diabetes risk and augment clinicians’ decisions on when to schedule patient appointments.

The approach uses machine-learning to analyze electronic health records, along with U.S. Census data on income, education and other socio-economic variables.

“It doesn’t schedule appointments at a specific time,” Ye says. “Instead, it provides recommendations for appointment frequencies to the healthcare provider. For example, based on the patient’s clinical records and socio-economic background, we would suggest how many encounters this patient should have with a healthcare provider in the next six-month period.”

The research indicated that the data-driven predictive framework could reduce risks associated with diabetes management by 16.3% for all population groups and by 19.4% for more disadvantaged groups.

Ye says the research could have practical implications for healthcare providers.

“Providers need to really pay attention to the patient demographic and socio-economic characteristics, because those could indicate different behaviors in engagement with the care providers and that can lead to different care outcomes,” Ye says. “So when providers implement their care, they could think about customized or personalized strategies to engage the patients and try to reduce the disparity in access to improve their engagement.”

The research is published in the Journal of Operations Management.

Even More Healthcare-Related Research

Felipe Augusto de Araujo, assistant professor of economics, et al. Research results suggest that on-the-job medical experience mitigates, but does not eliminate, base-rate neglect, a common bias in assessing conditional probabilities such as those involved in interpreting test results.

Jee-Hun Choi, assistant professor of economics. New study examines how the breadth of provider networks affects Medicaid beneficiaries’ access to and utilization of outpatient care services.

Chad D. Meyerhoefer, chair, Department of Economics, and Bingjin Xue ’18G ’23 Ph.D. Research finds that when a healthcare provider adopts a new electronic health record system, primary care providers are more likely to refer their patients to specialists using the same system.

Andrew Olenski, assistant professor of economics, et al. Research finds nursing homes in Illinois might be obscuring profits reported to government regulators by making inflated payments for goods and services to related companies.

David Peng, Dean’s Chair Professorship, DATA, and David Zhang, associate professor, DATA, et al. Research introduces a novel machine-learning framework to derive text-based indicators of physicians’ professional ethics using online patient reviews.

David Rea, assistant professor in DATA, et al. Research finds that ER physicians innately alter their behavior based on operational factors. The physicians order more medical tests when they have limited time to spend with patients, such as at the end of a chaotic shift; when less busy, they prefer time with patients to testing.

Jacob Zureich, assistant professor of accounting, and Manasvini Singh, of Carnegie Mellon University. Research finds physicians improve more from positive feedback; negative feedback resulted in no improvement or hurt performance.