Story by Margie Peterson

Image by iStock/EireenZ

Felipe Augusto de Araujo wants to know if you’ll pay more to feel better about a product.

You’re at the supermarket and you see carrots labeled “USDA Organic,” or you buy lightbulbs marked “Energy Star.” What do those labels really mean and is it profitable for companies to earn them for their products?

That was the question Felipe Augusto de Araujo, assistant professor in economics, sought to answer with research about how consumers perceive those labels and whether they will pay extra for such “higher standard label” products. Working with fellow Lehigh Business economics professors James A. Dearden and Ernest K. Lai, and with recent graduate Ben Murphy-Schmehl ’24, Araujo set up a series of experiments in which participants could choose to buy products carrying labels that made consumers feel better about their purchases but also cost more.

The idea grew out of conversations Araujo had with Murphy-Schmehl, who as a student had worked in Lehigh University’s Office of Sustainability, where he observed that people in offices and departments on campus liked being awarded different colored badges for good environmental practices, such as using recycled paper and environmentally friendly printers. But few people other than those awarding the badges seemed to know what the standards were to earn each one.

That’s not surprising given that product labels attesting to good environmental practices abound in society, with more than 450 registered at ecolabelindex.com. That proliferation makes it hard for consumers to know which labels to trust, Araujo says.

Entities that label products for sustainability include governments and non-governmental organizations, with some industry-backed groups that may set lower standards for earning their labels.

Araujo focuses on externalities, which are instances in which the actions of one party affect the lives of others not involved in the transaction.

“We all know that market exchange often leads to negative externalities,” Araujo says. “You can think of pollution, labor exploitation and unsustainable resources to name a few.”

Yet typically, people don’t know the environmental effects of the manufacturing or growing of a product when they buy it. That’s where the standards for labels come in.

“The consumers would like to know exactly what it is that this coffee company, for example, is doing differently than the other one,” he says. “That’s the holy grail.”

Using the Lehigh Business Behavioral Research Lab, Araujo and the researchers created a simulated marketplace. They designed and conducted experiments over 18 sessions with 18 paid participants in each session for a total of 324 people. Each took a randomly assigned role of buyer, seller or third-party participant who would bear the brunt of the negative externalities, such as pollution.

“So now buyers know that if they buy a product that is really bad, environmentally speaking, they’re going to be responsible for a cost—a monetary cost—that is going to be imposed on a third party,” Araujo says.

The buyers entered the market and saw each product’s label status and price and then decided whether to buy. If the product was one with a high negative externality, the third-party participant suffered the cost. For medium externalities, the third-party participants lost some money and for low externality, it was no cost.

The research team ran the experiment with different conditions, including when the consumer knew the standard was low for earning the label and when it was high.

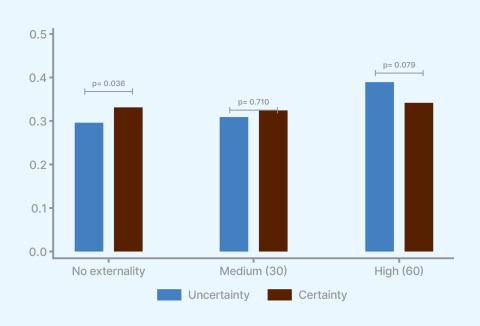

Araujo says they found that when consumers knew what the label’s standards were, they were willing to pay more for the product with the label. In addition, more sellers were buying labels when the labeling criteria were certain.

Why it Matters

Companies can charge more for products with sustainability labels and consumers will pay more for those products if the standards for sellers to earn labels are clear.