Go to homepage

Go to homepage

A new law that makes California the first state in the nation to require publicly held corporations to include women on their boards sends a clear signal that corporate boards across the United States should heed.

And they should do so with a sense of urgency.

In recent years, the number of female directors on corporate boards has moved at a glacial pace. Even with women accounting for a record high 38.3 percent of new board members appointed in 2017, women held just 22.2 percent of all Fortune 500 company board seats—up just 1.2 percent from the previous year.

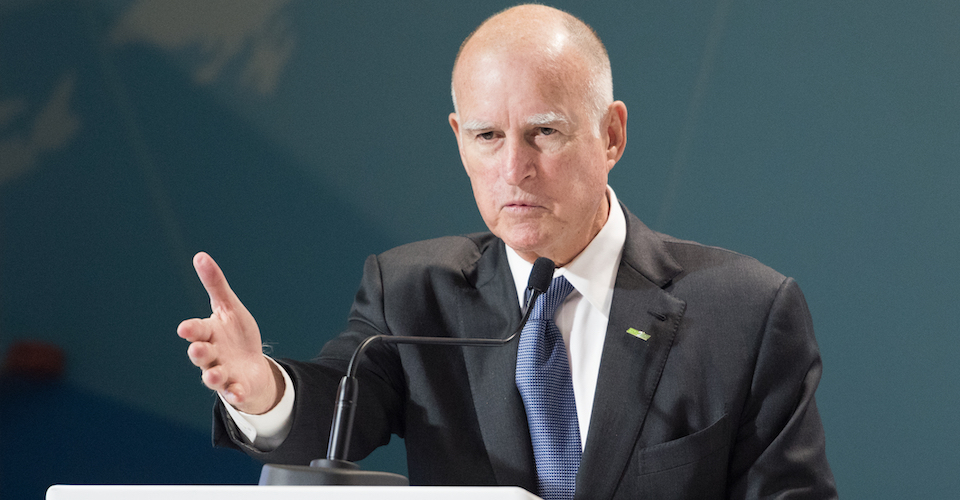

The California law, passed by the legislature in late August and signed into law by Gov. Jerry Brown on Sept. 30, offers a short-term solution to address the lack of real progress in increasing the role of women in corporate decision-making at the highest level.

The law requires publicly held companies “whose principal executive offices” are in California to have at least one woman on their boards by the end of 2019. And depending on the size of their boards, those companies must have a minimum of two to three women board members in 2021.

Some critics contend that establishing “quotas” by law will do more harm than good, leading those inside corporate organizations to question whether a woman has been appointed because she’s qualified or because the company needed to fill a quota. It’s funny, though, how nobody questions whether male directors are the “most qualified” when they are put on boards. For example, Tesla’s board is composed of co-founder and CEO Elon Musk’s longtime friends, business partners, and brother.

Provided a quota or requirement comes with clearly spelled out qualifications and qualities needed for all candidates to enhance the board, I think they can have a positive effect.

Reviewing and making clear the qualifications and qualities required for a director would benefit the entire board, and likely change the narrow search criteria that focuses on CEO experience as a board prerequisite. For example, firms that determine they need directors with digital experience tend to bring more non-CEO directors on board.

As a Harvard Business Review article stated: “The scarcity of digital talent with CEO experience, however, has provided open-minded companies with the opportunity to shift the traditional makeup of the boardroom; women account for 58% of the digital nonexecutive directors (NEDs) recently added to boards.”

Gov. Brown, in his signing statement, also acknowledged that the law raises “serious legal concerns” that “indeed may prove fatal to its ultimate implementation.”

Still, in a sense, it represents an important first step. After all, California is not only by and large the largest economy in the U.S., it is the fifth-largest economy in the world.

In addition to prompting serious questions about the qualifications and qualities needed on the board, the law should also awaken corporate boards across America from their lethargy and persuade them to begin the hard work of identifying female leaders qualified for board appointments and implementing the changes needed throughout their organizational cultures to provide more opportunities for women to gain the experience and skills needed to excel at the top.

A clear message is being sent that if they don’t, the government may take the decision out of their hands.

Ideally, of course, corporations would have seen that increasing diversity on their boards was in their own self-interest and taken action on their own years ago. But that hasn’t happened—despite evidence of the benefits of having women on boards.

Along with my colleague Kris Byron of Georgia State University, I have conducted separate meta-analyses examining the relationship between women on corporate boards and a firm’s financial performance or corporate social performance.

In Women on Boards and Firm Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis, published in the Academy of Management Journal in 2015, we analyzed data from 140 separate studies representing roughly 90,070 firms in 35 countries on five continents.

As we wrote in our study, we found that “boards and firms seem to derive a benefit from female board representation and that the presence of women on a board can be leveraged for higher accounting returns.”

“For boards and firms, our findings suggest that board gender diversity is not a simple ‘numbers game.’ For the presence of female directors to yield higher accounting returns, our findings suggest the importance of developing a board culture in which dissenting voices are heard and considered,” we wrote.

In Women on Boards of Directors and Corporate Social Performance: A Meta-Analysis, published in Corporation Governance: An International Review in 2016, we analyzed 87 independent samples. As we wrote, “our finding that firms with women on their boards tend to be more socially responsible provides a compelling rationale for continuing to work at improving the representation of women in governance.”

And we found that while having females on corporate boards was generally positive, “this relationship is even more positive in national contexts characterized by higher stakeholder protections and gender parity.”

That’s why the new California law, as significant as it is, represents just a first step. Our hope, as stated in our latest study, is that “efforts [will] be directed at improving the status of women in society and in the workforce, for example, enabling women to reach the highest levels within their organization and holding boards more accountable toward shareholders and, ultimately, toward all stakeholders.”