Go to homepage

Go to homepage

To paraphrase the late U.S. President Ronald Reagan, there they go again.

Once more, we’re being told that cutting tax rates will spur productivity and economic growth —one of the prime tenets of the Reagan presidency in the 1980s. For more than three decades, the argument has been that if you cut tax rates, particularly for those in the highest income brackets, the wealthiest Americans will invest the money they save and that investment will find its way into capital equipment and boost the productivity of workers, while also creating new jobs.

The promise has always been that tax cuts pay for themselves. How? We’re told that cutting taxes will spur rapid economic growth, which in turn will expand incomes. So even though the tax rate is lower, proponents say, incomes will rise to a level where people actually pay more in taxes. The result, the argument goes, is more revenue, not less.

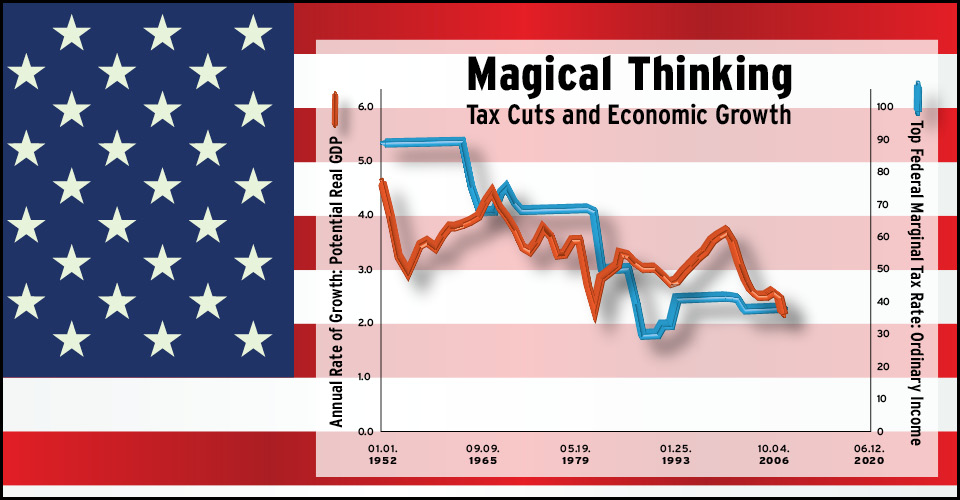

Looking at the facts over more than six decades, that seems more like magical thinking than sound economics.

It’s hard to imagine now, but the top marginal tax rate was at 90 percent or higher from 1951 to 1964, when it was lowered into the 70 percent range. It remained in the 70s throughout the 1970s, until the first Reagan tax cut slashed it to 50 percent in 1982. In the late 1980s, it dropped as low as 28 percent, before increasing again into the low 30s and, by the 1990s, up near 40 percent. Since then, the top marginal tax rate has ranged between 35 percent and just under 40 percent.

Over more than 60 years, then, the top marginal tax rate has been cut precipitously and repeatedly. So if the argument is true that cutting taxes spurs economic growth, you would logically expect that each time the top rate has been slashed, economic growth has soared.

That didn’t happen. In fact, government debt has soared. And the reason is simple, as illustrated on the accompanying chart: There is no basic relationship between productivity growth, which is the primary driver of economic growth in the U.S., and taxes.

As the chart shows, productivity growth stays within the same basic range whether the top tax rate is 90 percent or 28 percent. Within that range, economic growth did rise corresponding with the Reagan tax cut. But it also rose at a greater rate after the tax rate was raised in the 1990s. Don’t misconstrue my meaning. I certainly am not saying that raising taxes spurs economic growth. And I wouldn’t say that taxes don’t matter.

But it seems pretty clear to me that if taxes are important, they’re important at the margin—not as a prominent driver of economic growth. And while I’ve been talking specifically about the personal income tax, the same is true if you look at the capital gains and corporate tax rates over the same period. There is little, if any, relationship between cutting those tax rates and productivity growth.

There are other factors that are far more important, including the rate of research and development, technological innovation in products and processes, innovation in management, and the drive from entrepreneurs to create new businesses and reap the rewards, to name a few.

Could you imagine Steve Jobs in his father’s garage in Cupertino, Cal., as he built the first Apple computers with partner Steve Wozniak in the mid-1970s, saying, “Damn, you know this is a really good business idea, but the top marginal tax rate is 70 percent, so I don’t think I should pursue it.”

More likely, he was saying, “I sure hope I get to be in the 70 percent tax bracket! That will mean my idea was really good and I became really rich as a result.”

If we’re going to talk about tax reform, let’s have an honest discussion about the potential merits and drawbacks of the plan, and not pretend that this time, lowering taxes on high incomes will—like Jack and the Beanstalk—magically spur economic growth and more revenue.