Go to homepage

Go to homepage

Editor’s Note: This is the second of two parts looking at the rationale and possible impact of income tax reform. Read Part One: Why We Need True Tax Reform

The Trump administration announced its plan for what officials are calling “the biggest individual and business tax cut in American history” this week.

While the timing of the president’s announcement was a surprise, the contents of his plan were not. They generally mirrored what he has been saying for months. Speaker Paul Ryan and House Republicans also have promised comprehensive tax reform. In fact, the House released its 35-page blueprint last summer.

So what can we infer at this early stage, based on what has been published?

President Donald J. Trump’s plan, as it was rolled out in a one-page document in Wednesday’s press briefing, consists of three individual tax brackets: 10 percent; 25 percent, and 35 percent; and a doubling of the standard deduction. That would mean, for example, the first $24,000 of a couple’s taxable income would be exempt from taxes. Many details, such as the income ranges for the new tax brackets, will be worked out in negotiations between the White House and Congress.

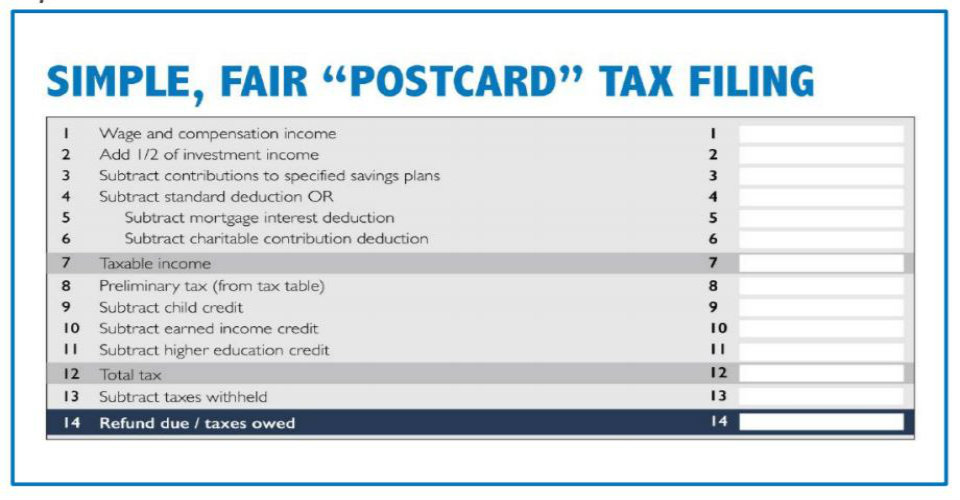

The president’s plan regarding tax rates is very similar to the House version, which also provides for new, higher combined exemption deductions of $12,000 for singles ($18,000 with children), and $24,000 for couples filing jointly, and also consists of three tax rates: 12 percent, 25 percent, and 33 percent. The House plan has a stated goal of simplifying the tax code so that most Americans can file their taxes on a postcard form, similar to the version below included in their plan:

The plans are similar on several other points as well. Based on Wednesday’s press briefing and the more detailed version of the president’s proposal posted earlier this year, as well as last summer’s House blueprint, the most striking features of these plans include:

First the good news. The Tax Foundation projects that–depending on whether they studied the president’s plan (as outlined during the campaign) or the House plan, and whether static or dynamic modeling was used—taxpayers would see an average increase in their after-tax income of between 1 percent to 10 percent in total over 10 years.

However, the top 1 percent would benefit the most, with the wealthiest taxpayers seeing an increase in their after-tax income of 5 percent to 20 percent. That should not be a surprise. After all, the top 1 percent pay almost 40 percent of the individual tax receipts and are the ones in the higher 35 percent and 39.6 percent tax brackets. So it stands to reason they would gain a lot more than the average taxpayer.

Perhaps what will be more startling to the average voter when tax reform starts to get more press coverage is that, according to the Tax Policy Center:

A significant part of the cost of the above would be offset by broadening the tax base through the elimination of many deductions and credits, the loss of business interest expense deductibility, the loss of the domestic manufacturing deduction, and possibly a tax of some type on imports. However, all independent analyses of the above proposals indicate that there would probably be trillions of dollars added to the federal debt over the next 10 years

The Tax Foundation estimated that both the president’s plan (as outlined during the campaign) and the House plan would probably raise real Gross Domestic Product (GDP)—a leading indicator of economic health—by about 1 percent annually, from the current 2 percent to 3 percent. But both plans would also increase the federal debt by anywhere from $200 billion to possibly $6 trillion over a 10-year period, depending on which plan they studied and whether static or dynamic modeling was used.

And the Committee for a Responsible Budget estimates that the president’s plan announced Wednesday will cost $3 trillion to $7 trillion more debt over the next 10 years.

There is probably no chance the Democrats will be on board with any of this, at least until the president is willing to release his tax returns. Even ignoring that political impasse, let us assume that: a) health care reform is passed; b) the president can actually work with the House and Senate Republican leadership to negotiate the details with the Treasury Department; c) the negotiations can survive the scores of special interest groups, who may perceive themselves as the “losers;” d) the president does not create any more self-inflicted distractions and can stay focused on tax reform; and e) we avoid global wars.

Even if all that occurs, there would still be two huge hurdles to passage:

With all this in mind, I am not personally optimistic of passage in this Congress. Moreover, even if it does pass, no reputable study has yet suggested that it can help mitigate the growth in the national debt from the present $20 trillion to $30 trillion over the next 10 years.

Perhaps that will come another time, or with another president, or after we somehow fix our broken governing institutions. But one has to wonder: If they cannot get it done with the White House and both houses of Congress controlled by the same party and everyone wanting tax reform, can they get anything meaningful passed?